Forting Utopia – Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2019

Forting Utopia – Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2019

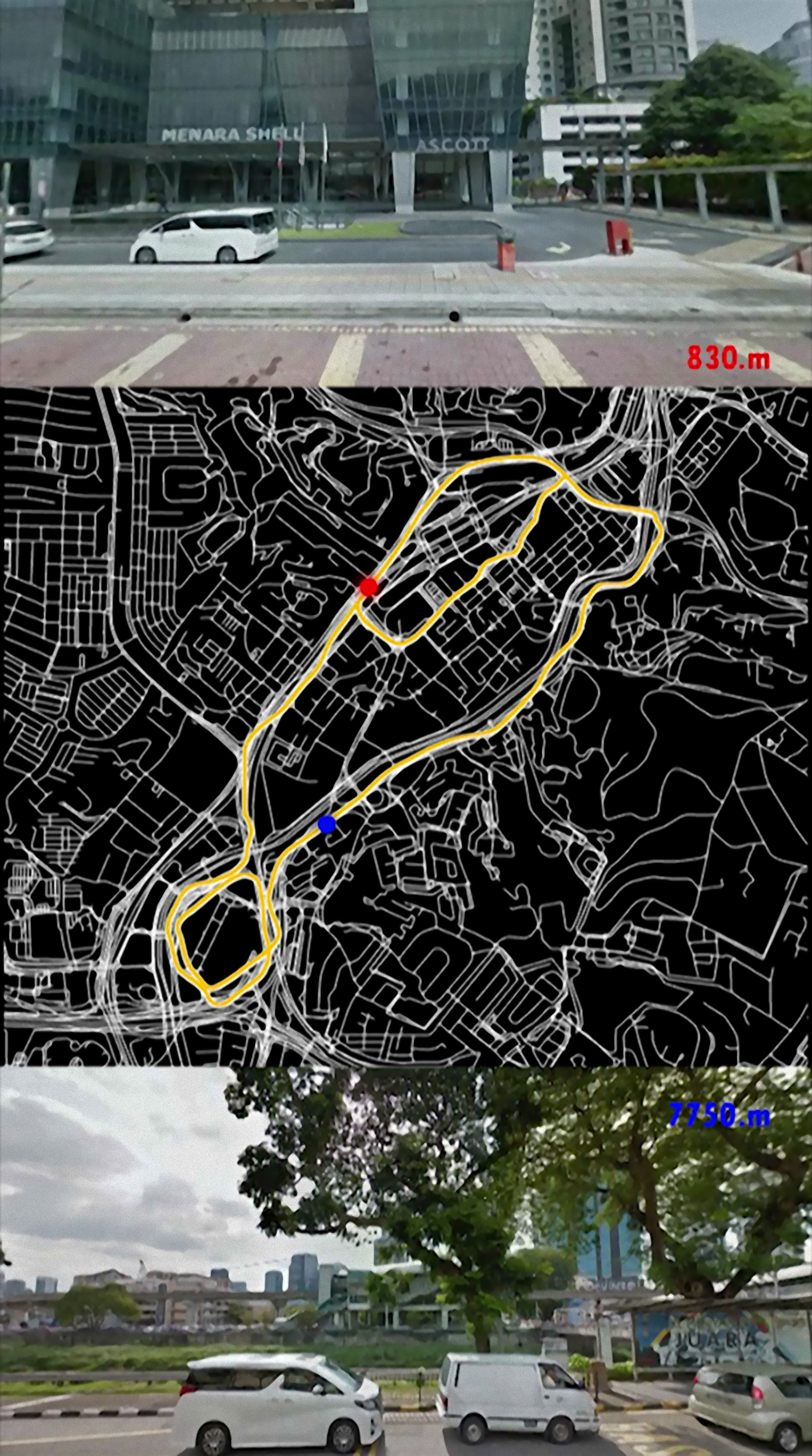

Kuala Lumpur, popularly abbreviated as KL, is, like many of its Asian counterparts, a rapidly urbanizing and global city with a multitude of challenges that are typical to any major city in the developing world. Oftentimes it is misconstrued as hodgepodge or schizophrenic, which leads many to believe that it is poorly planned and leaves much to be desired as to what a contemporary city should be. However, the urban planning challenges that KL faces is rather unique, and there are not many models for it to draw from. In fact, its challenges can be overtly observed in many ways—via satellite images, figure ground diagrams, street photography, etc.—and they tell the same story: that the cacophony and unrelenting assemblages of disparate parts at all scales form a complex socio-cultural milieu that cannot be pigeonholed into traditional urban planning axioms. To put it bluntly, there does not seem to be any viable strategy so far to guide KL into becoming a distinct global city.

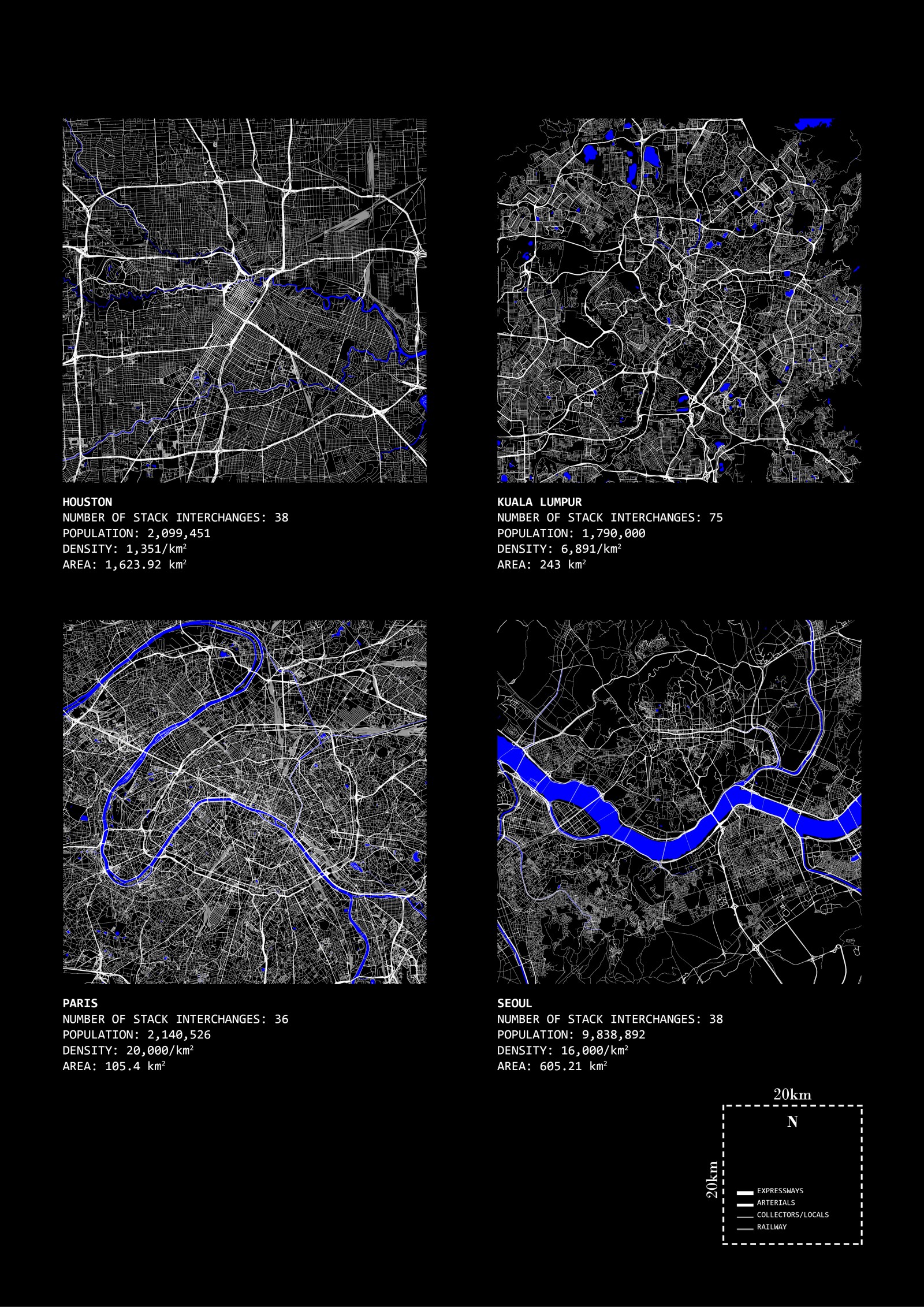

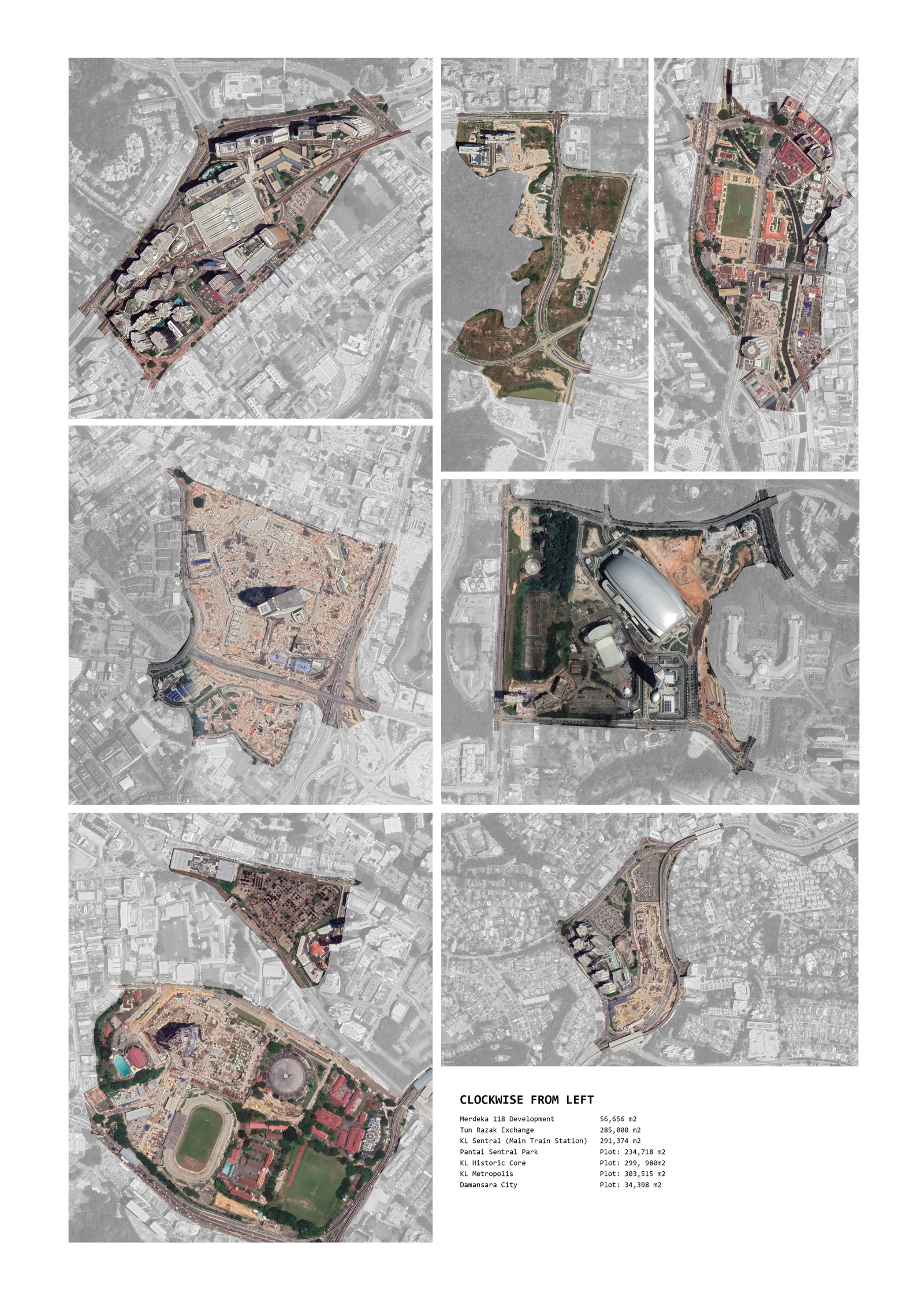

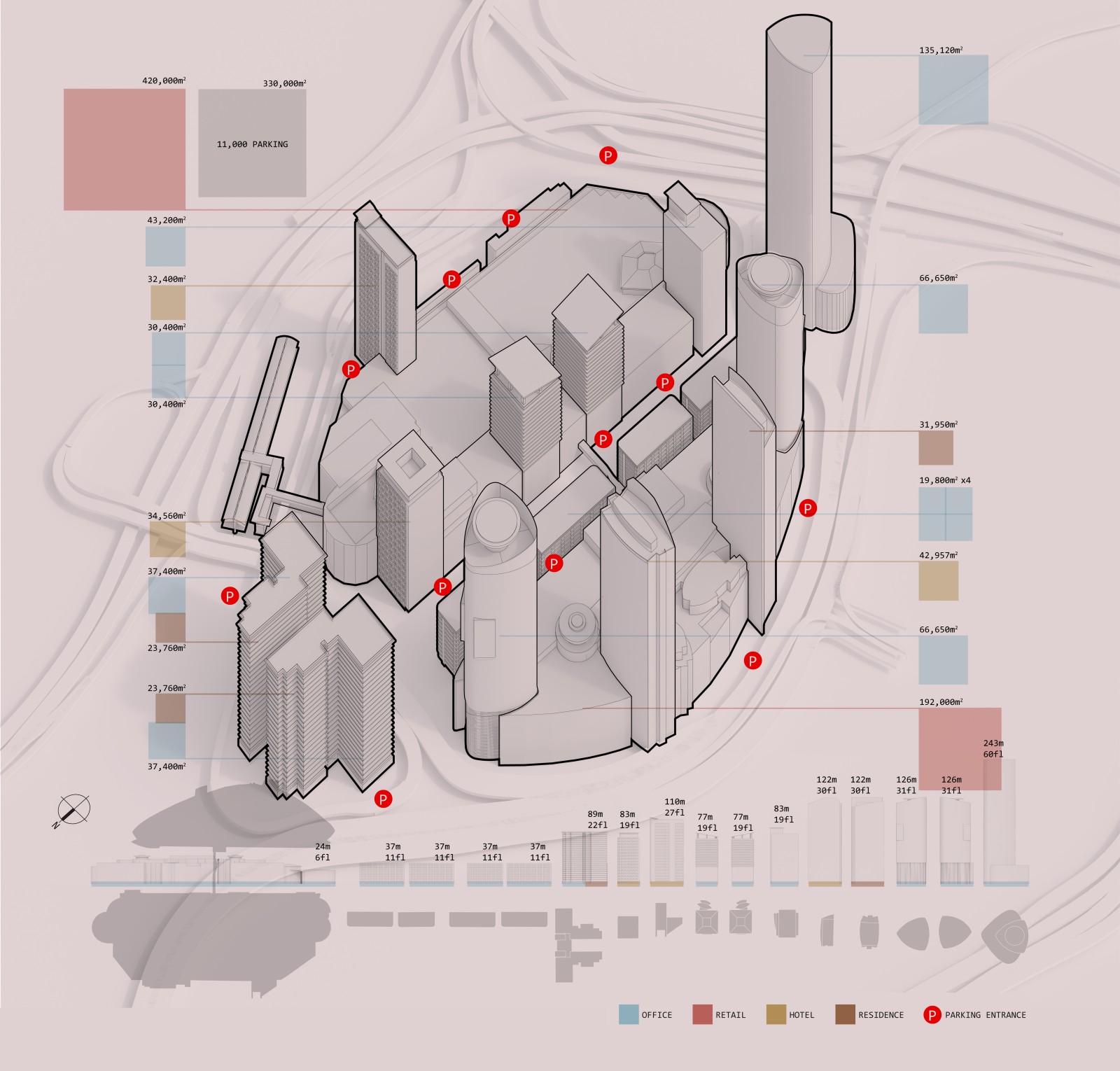

Luckily, the multifaceted nature of such a city allows one to engage in multiple readings of the city, and to disentangle from the textbook understanding of what cities ought to be, or whether they should be acquiescent to the trendy tropes of today’s so-called livable cities. In recent years, KL’s resurgence as a real-estate engine has resulted in a boom in integrated mixed-use developments that are almost identical to many other similarly developing cities. As the financial capital, it has been the center of Malaysia’s economic miracle since the 1980s, spearheaded by a homegrown automobile industry, advances in manufacturing and financial sectors, and one of the largest per-capita infrastructure investments in the world.

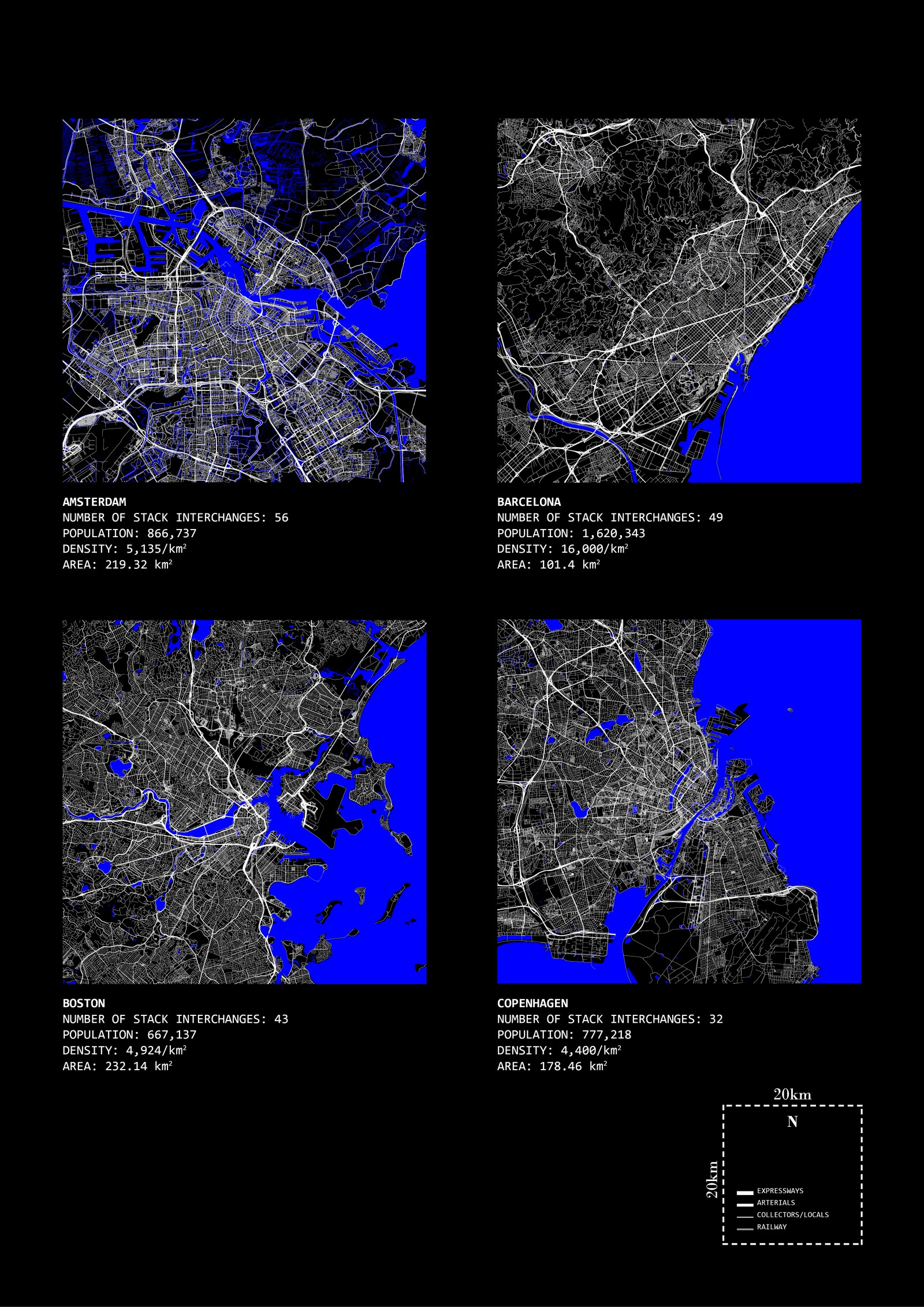

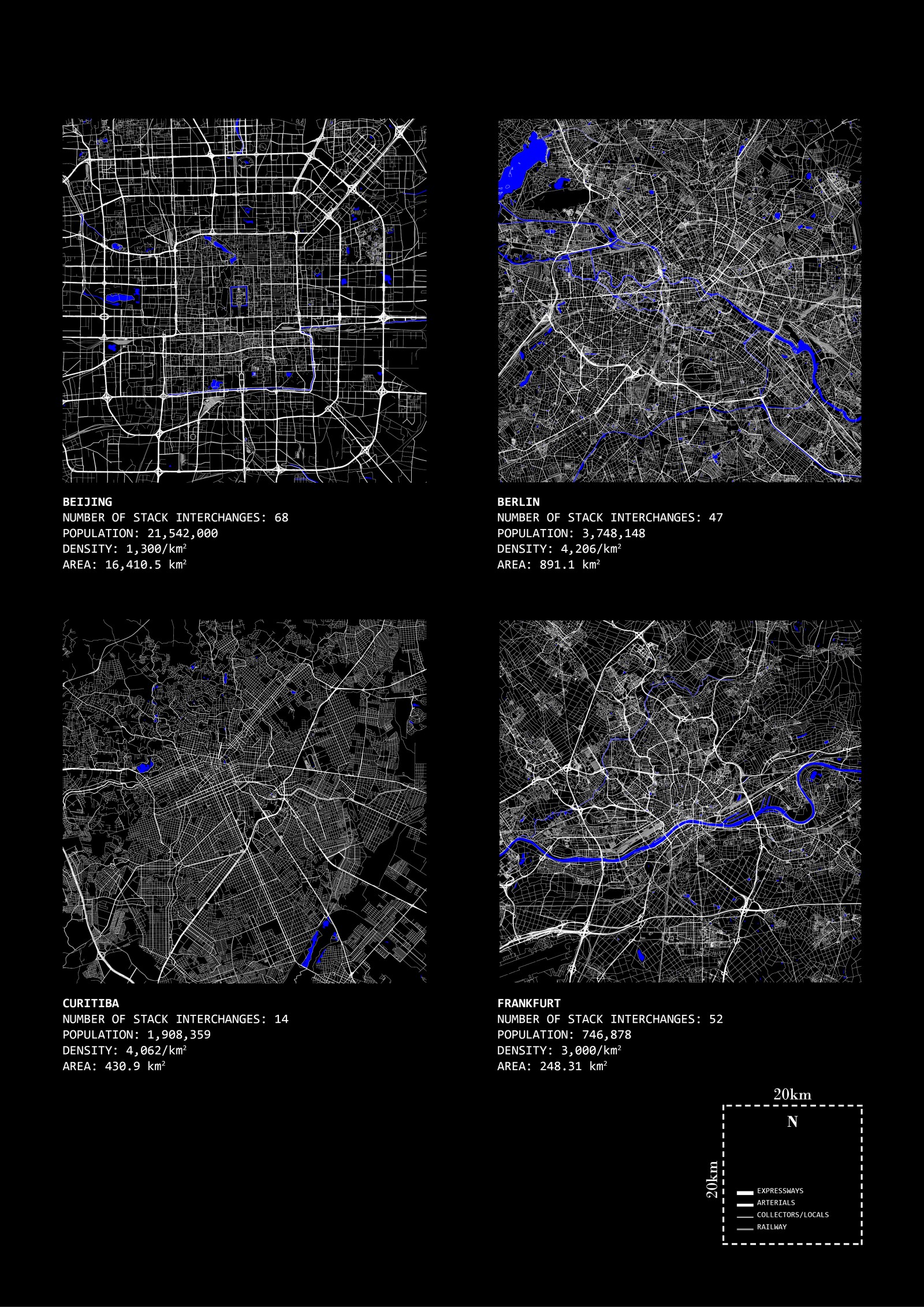

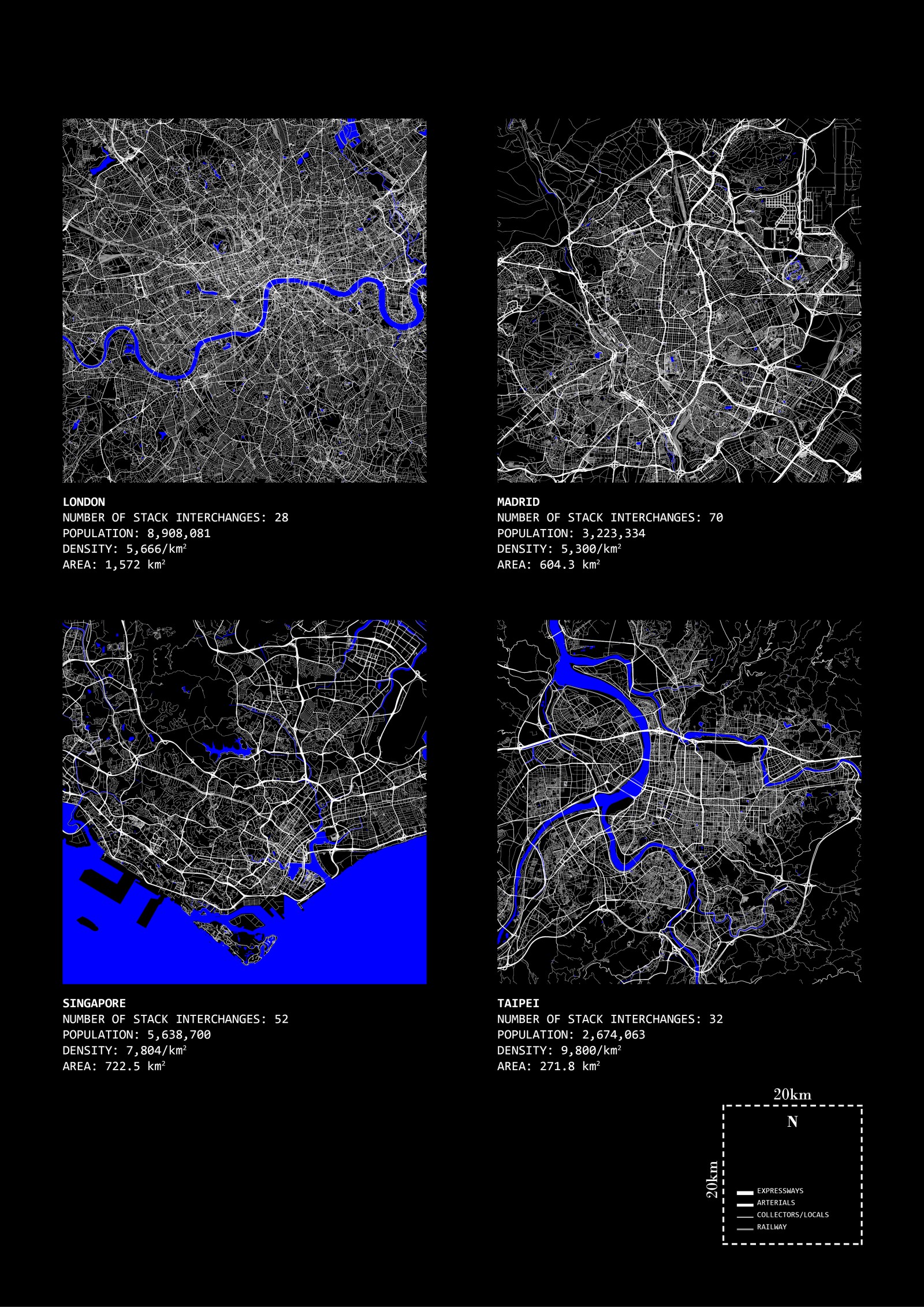

A complex series of policy decisions resulted in a desire to break from the traditional pitfalls of highly developing cities (traffic woes, housing supply, urban identity, etc.), but retain the universal doctrines of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City planning as outlined by KL’s first town planner Charles Compton Reade (1880–1933). Today, the city’s road and rail connectivity network has far outpaced all other forms of urban development and has inadvertently shaped the physicality of the city.

One such way is its unusual organization into large districts that are bounded by major arterial roads or highways. These connective networks are effectively physical and psychological barriers that coincide with local sub-districts, historical demarcations, natural topography, and recently the basis for the city’s metro rail network. These bounded “islands” are highly desirable places to live, work, and play, within a utopian vision as marketed by savvy developers. This vision is accentuated by what it is keeping out: the noise, dust, and the pauper. The motorways thus take on a dual role as the mechanism that ferries participants into a highly conditioned urban realm, while also a network of impenetrable no-man’s land.

It is not our intent to discuss whether this is a positive trajectory or not, but it is imperative that we understand this phenomenon that is rapidly defining the morphology of this urban region. The roads are here to stay, and our future discourse will be to dive into KL’s specificities that allowed this mode of placemaking to be favored, and maybe even desirable, in KL.

-

Date

September 1, 2019

-

Location:

Seoul, South Korea

-

Year:

2019

-

Status:

Completed

Share project